Extremely brief reviews to break an extremely prolonged silence

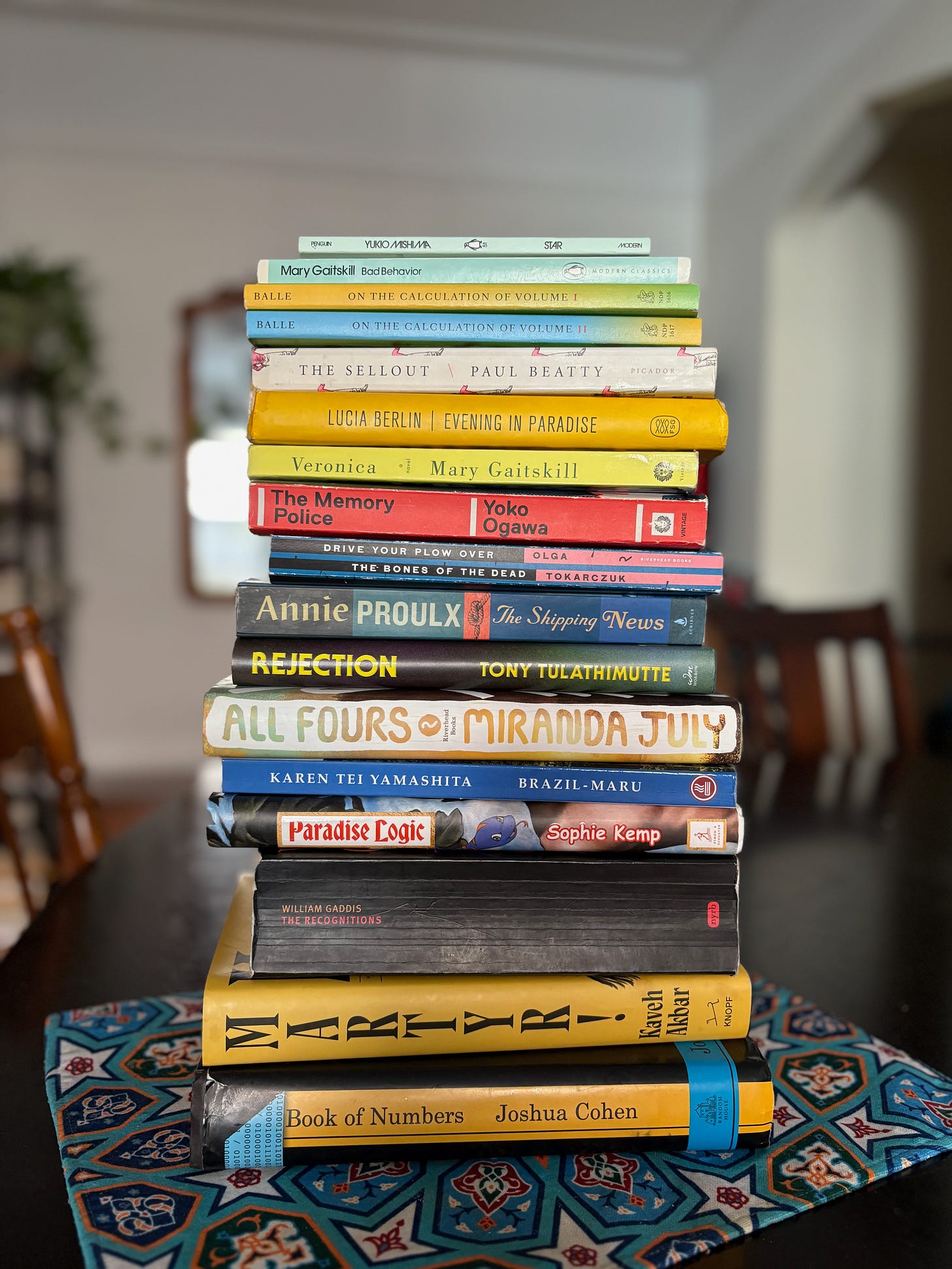

a list of short recs (and anti-recs) of everything I’ve read in a year and a halfish (except the stuff I forgot)

Summer is a time for leisure, for hobbies, and, as marketing copy and public education alike will tell us, reading. Thawing is more of a spring metaphor, but the point is that I am defrosting something I’ve long had on ice.

I laid out certain rules when I set up the book blog, and even though I gave myself explicit permission to break said rules, I unfortunately love rules and am not going to do that. So I can’t just dive straight in with a full entry on the most recent book I’ve read (Veronica by Mary Gaitskill, which appears at the bottom of the forthcoming list). Since I said that this blog would chronicle the fiction books I read in the order that I read them, here is a list instead of my spring, summer, fall, winter, and spring-again reading, from the last-year-and-something, theoretically in the order of consumption, with extremely brief reviews.

Note: For visual clarity, I’m putting a little star next to a title if I’d say I recommend it, but this is imprecise and I’d recommend different things to different readers, so.

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa — Perhaps this book is somewhat to blame for the stalling of my blogging, because it was totally fine in a way that I found difficult to remark on. Pretty good for sci fi, but I don’t really like sci fi. The world in the novel has a muffled ambiance that came to mind again when I read On the Calculation of Volume I + II (later in this list). There’s a romance plot that worked for me.

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar — Junot Díaz deceived me. Calling Akbar “a dazzling writer, with bars like you wouldn’t believe,” he admits that there are sections that “feel more researched than vital and often overstay their welcome” and “a couple of coincidences too incredible to believe.” But “in spite of these stumbles,” Díaz writes, “what Akbar pulls off in ‘Martyr!’ is nothing short of miraculous.”

I read this one because the reviews made it sound incredible, and I found myself…incredulous. (The New York Times, which published Díaz’s take, ranked it one of the 10 best books — out of all books! — of 2024.) It’s true there are good lines and vivid scenes. The word technicolor captures the vibe — and not exclusively because Akbar uses actual television characters, like Lisa Simpson and Donald Trump, in the book’s frequent and extended dream sequences. (Side note: I’m on the hunt for ghastly, grimace-inducing depictions of the current and former president in literature, if you have any recs. In this book, Trump is referred to as “President Invective,” which makes me feel like this.)

I’m often here for cartoonish shit of truly Looney Tunes-level proportions, but this novel struck me as less funny than just cheesy, and those “couple of coincidences” are too much to bear. (The big one is painfully obvious by the book’s halfway point; I will spoil it for you if you ask.) Though I disagree with Díaz’s “miraculous” conclusion, I can imagine he might be flattered by novel: I wouldn’t be surprised if it was influenced by The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. You’re better off reading that.

★ All Fours by Miranda July — This time, contemporary fiction triumphed. (NYT top 10 somewhat redeemed!) I was primed to love this because I’m a longtime Miranda Julyhead, but I really do think it lived up to the hype. As a woman still quite far away from perimenopause (tyvm), I felt, yes, the future-based anxieties of femininity resonating throughout it, but always clothed in the uniquely weird and hilarious Miranda July dressing that I personally love. July takes entirely plausible, quotidian scenes and lets her socially warped characters manipulate them until they’re so strange they feel surreal, even though everything that’s transpired is technically, physically, possible.

The Shipping News by Annie Proulx — I wanted to like this more than I did. It’s at times lyrical and kind of touching, but also plodding, and ultimately just did not do what I want fiction to do.

★* The Recognitions by William Gaddis — I probably should have blogged this one in installments while I was reading it. I’m glad I read it. Think resonances of The Picture of Dorian Gray and Hamlet but blown up to almost the size of Infinite Jest. As the title suggests, it’s about what it means to be seen, known, or, y’know, recognized, and what it means to do the seeing/knowing/recognizing — in art, aesthetics, labor, love, family, and of course in death. It contains some of the most beautiful sentences I’ve encountered, which I read out loud to unwitting victims, like:

Day did not dawn. The night withdrew to expose it evenly pallid from one end to the other as a treated corpse, where the hair, grown on unaware of the futility of its adornment, the moment of the brown spot past, is shaved away like those early hours stubbled into being and were gone, and the day laid out, shreds of its first reluctance to appear still blown across its face where dark was no longer privation of light but the other way round as good, exposed passive and foolish at the lifting of chaos, is the absence of evil. The day existed sunless, its light without apparent source, its passage without continuity, not following as life does but co-existent with itself, and getting through it was to blunder upon its familiar features, its ribs and hollows, impotent parts and still extensions, with neither surprise, nor hope, like the blind man identifying with a memory-sensitized hand the body of a familiar in what they had both called life.

Did I enjoy it the whole time? No. This thing is a workout. There are extended, probably-several-dozen-page (but I’m not counting) chunks of unbroken, unrelenting dialogue, where speakers go unsignaled and you have to follow by either recognizing form or content (hard) or just remembering who spoke first. I learned words I never knew I didn’t know (and had forgotten again until I looked back at my sticky notes), like “Bathysiderodromophobia,” the fear of subways and the underground; “hypospadial,” the adjective form of hypospadias, a condition in which the opening of the urethra is on the underside of a penis instead of at the tip (spelling problems, I presume?); and “nostology,” the study of aging, senility, and the return to a childlike state late in life — an important theme, turns out.

*heavy caveating of this rec. Only for true freaks.

★ Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner — A book for leftists who like making fun of other leftists or really anyone who enjoys contemplating what happens when political ideology meets practical reality. It’s been dubbed a Kushnerian (my term) take on a spy novel, which it is, but it’s more interested in interrogating what can fracture or preserve a society than dodging lasers or dangling out of helicopters. It is at once breezy and intellectual and, yes, suspenseful.

★ Evening in Paradise by Lucia Berlin — I started this book of short stories when I lifted it from a friend’s forgotten tote bag, returned it (it was a library book!), and then had to go out and get my own copy because I so desperately wanted to keep reading. These are seemingly simple stories about things like love, sex, drugs, and death that present those themes with a kind of matter-of-factness that would seem detached if it weren’t so poignant. Like in one story, about a motorcycle racer (slash heartthrob) who dies in the process of giving a stunning performance:

What I am saying is that even with the shock of his death, even with the bike in flames, with Michael's blood on the concrete wall, his body, the shrieking and the sirens, it all had his particular throwaway insouciance. That it was the last race, and he had won it.

★! ★! ¡¡¡★!!! Book of Numbers by Joshua Cohen — I have to say it: If you’re like damn I wish DFW were still alive because I’d love to watch his brain melt onto the page over the internet-powered surveillance state, you have to read Joshua Cohen. This novel is a classic doubling-of-a-guy story taken to bizarre heights reachable only in the age of Online. A struggling, recently divorced, admittedly gross writer named Joshua Cohen (interesting…) signs up to ghostwrite the autobiography of an eccentric and dying tech titan also named Joshua Cohen (even interestinger…) who designed a web search interface so good it would alter the course of humanity. How ethically is any of this being handled? A clue perhaps lies in the fact that the real Joshua Cohen helped write Edward Snowden’s memoir.

In my view it’s the most exciting, hilarious, linguistically creative book on this list. And of the Cohen I’ve read (admittedly non-exhaustive!), it is the most Wallaced out. Example in this portion, where the writer JC is transcribing the life story of the tech JC, who refers to himself in the plural and to his parents as “D-Unit” and “M-Unit,” describing their divorce and the father’s undoing:

We had not known that D-Unit had been condoliving at The Clingers ever since we left the house. D-Unit had never told us and we are not even sure whether M-Unit or Aunt Nance had known. Of the mail we took in, what surprised us the most were the catalogs for exotic gamemeats and kits for homebrewing. Of the msgs on the voicemail we checked, what surprised us the most were the appointment confirmations from gun ranges and attendance requests from Hasidics seeking a minyan.

Either this was the true D-Unit, free from having to split everything with M-Unit and so free to psychically compensate by evincing a split within himself, or this was a newly single engineer in the midst of übercrisis. We will never have confirmation. Unit 26 at The Clingers. Apostrophe, possessive.

The father is a computer engineer (far less successful than his son will become), and the mother a comparative linguist. In other words: “The D-Unit we knew had always been a hardware guy, meaning that he regarded software as like unserious, or pretentious, as like the gyno-linguistic pedagogy of his wife.”

As I learned by googling to try to find the page to check the quote after I’d already transcribed it and failed to write down the page number, this section I’m quoting also appeared in Harper’s Magazine as an excerpt, if you want a more extended sample.

★ Rejection by Tony Tulathimutte — In my Book of Numbers hangover, I was just not ready to pick up another novel, so I turned to this book of short stories instead. The first three stories in here go painfully hard. Brace yourself for stress-you-out while-you’re-falling-asleep, remind-yourself-it-isn’t-real levels of secondhand embarrassment (plus genuine sadness!). The subsequent four stories fill out the book’s intertwined novelesque structure, but don’t quite pack the same punch.

Star by Yukio Mishima — I was promised I would be scandalized. I wasn’t. (Possibly also read this super short book too fast and didn’t process it thoroughly enough.)

On the Calculation of Volume I by Slovej Balle — The cult sensation that asked what if you were stuck reliving the same day, again and again, forever and ever, in perpetuity? left me thinking that I don’t know, I guess I would get pretty sick of it.

On the Calculation of Volume II by Slovej Balle — Then again, maybe I’ll read the forthcoming III.

Paradise Logic by Sophie Kemp — I read this with a book club and when I started I was pissed at my clubmates for suggesting it. This incredibly contemporary book has a grandiose narrator who at their worst sounds straight out of Reddit, with linguistic flourishes like that the main character was “bornth.” But it’s incredibly easy and breezy and without having to think about it much you’ll find that the book takes some trippy turns, plunging you into a surreal quest where hallucinatory imagination merges with whatever the novel might consider reality. (The main character’s name, by the way, is Reality.) By the end, I was ready to consider it better than I’d thought.

Brazil-Maru by Karen Tei Yamashita — This book does what we ask of historical fiction, which is to say provide an immersive, character-driven account of what a particular past phenomenon was like. I learned a lot about the Japanese settlers in early-to-mid 20th century Brazil and wrestled with questions about communal living and its limitations. But I didn’t find this as funny or inventive as Yamashita’s Tropic of Orange or, my favorite of hers, I-Hotel.

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk — Maybe not the Tokarczuk book I should’ve read. A book with strong ecofeminist themes, if not an explicit argument, that leans heavily enough into its murder mystery plot structure to distract from the genuine weirdness of its unreliable narrator, a solitary old vegan astrologer who lives in the woods. There are moments when the prose sings and the scenes are genuinely hilarious (e.g. a backwoods dentist who practices outdoors for a crowd), but I got sick of waiting around to learn who killed various horrible men, both because it becomes pretty obvious, and also because they’re all too flatly horrible to give me any reason to care.

★ Bad Behavior by Mary Gaitskill — The debut book of short stories by one of the preeminent short story writers still writing and asking difficult questions. These stories are sexy and sad, tender and cutting, funny and depressing. A favorite of mine is called “Trying to Be,” and that’s pretty much the theme of the book: The characters are all grasping — for love, success, understanding — and never quite getting what they yearn for, but missing no opportunities to viciously judge everyone else along the way.

★ The Sellout by Paul Beatty — Probably the most solidly reliable on this list to make you wince (in a good way) and laugh. But the thing it’s not pure comedy. It clothes controversial political questions in satire and dazzling lyricism (the fact that Beatty is also a poet is clear, again in a good way). It asks what it really means to thwart society’s unrelenting racism, or if such a thing is even possible, and if and when it’s worth it to transgress the norms that are supposedly in place to keep you safe. It’s also a love story that casts the protagonist’s love in several directions: for his ex-and-current-girlfriend, an old man and lifelong friend, his hometown, his dead father, and a main antagonist too pathetic to be evil.

★ Veronica by Mary Gaitskill — Gives lie to the fact that she’s known as a short story writer, because this novel blows the aforementioned short stories out of the water. It consists of roughly three-ish timelines running on parallel tracks, allowing the narrator to merge seamlessly between them, often with little to no signaling. “Shadows of night sound solemnly glimmer in their rain puddles; inverted worlds of rippling silver glide past with lumps of mud and green weeds poking through,” Gaitskill writes. “The past coming through the present; it happens.”

If the glittering prose weren’t enough, the fact that this is (probably) the most poignant meditation on friendship I’ve ever read would be. It’s not that the narrator, Alison, immediately likes her friend Veronica. “Her voice on appreciate was like the rough tongue of a cat absently licking a kitten on the head,” Alison notices early on. “I could not help raising my head to meet it.”

Surely I haven’t done any of these books justice—and, for some of them, far less—but that is my list. I would say to look out for the next entry soon, but the book I’m currently reading is a solid two inches thick, so probably don’t.